Shruti Dagar, M. Optom.

PhD Scholar, Assistant Professor, Sankara College of Optometry, Ludhiana, India

The human body is an intricate network of interconnected systems, and we are continually discovering new ways these systems influence one another. While the eye has long been viewed as an isolated organ, protected by its own unique barriers, recent research has unveiled a surprising and profound connection: the “gut-eye axis.” This emerging concept links the health of our digestive tract to the inflammatory conditions of the anterior segment of the eye, offering a completely new lens through which we can understand and manage common diseases like dry eye and meibomian gland dysfunction. It shifts our focus from simply treating symptoms to addressing the systemic root cause of inflammation.

The Gut-Eye Connection: A Mechanism of Inflammation

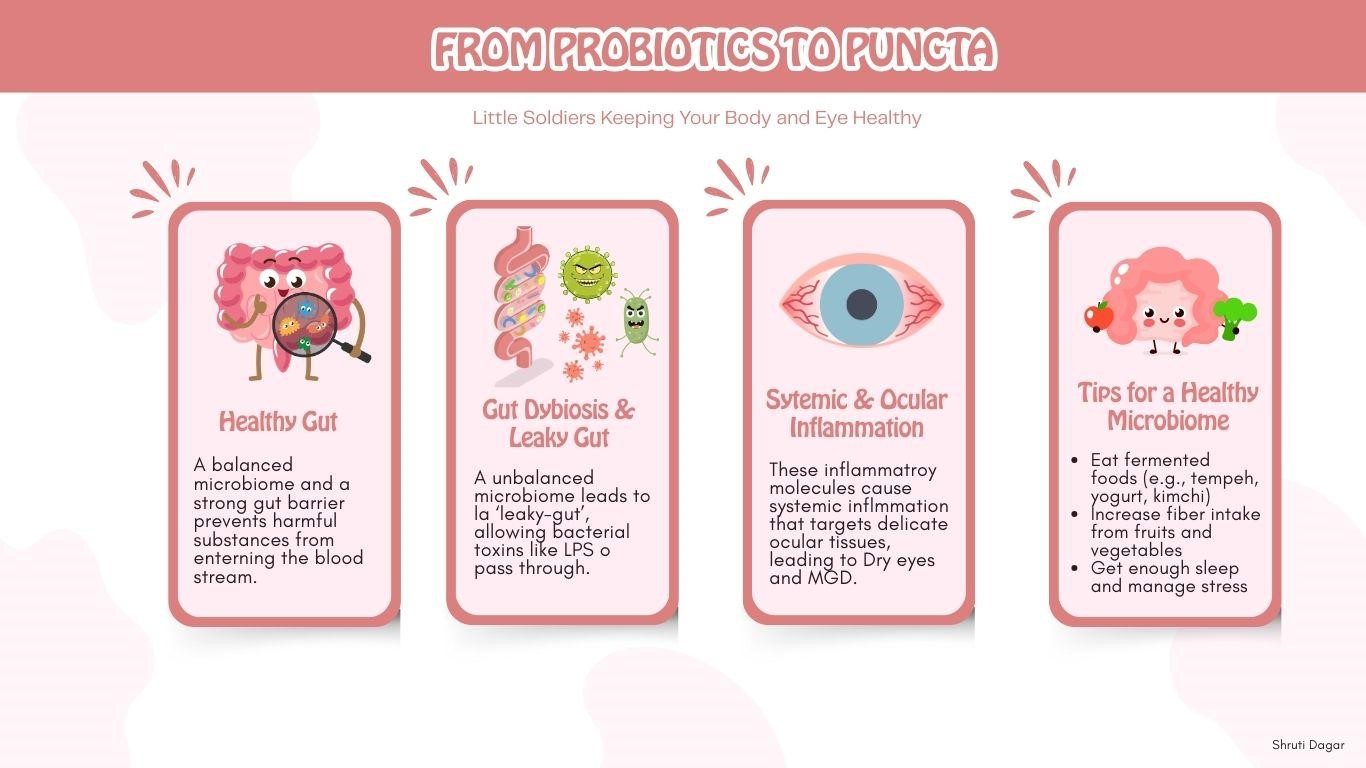

At first glance, the gut and the eye seem to have little in common. However, the connection is rooted in a shared immunological and inflammatory response. This connection is mediated primarily by the gut microbiome, a complex ecosystem of microorganisms that influences host health. When the composition of this microbial community is disrupted, called dysbiosis, it can lead to a breakdown of the intestinal barrier. This is the “leaky gut” model. Under normal conditions, the gut lining is a tight, selective barrier. However, dysbiosis can compromise this barrier, allowing bacterial products, such as Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and other inflammatory molecules, to leak into the bloodstream. (2)

Figure 1: From Probiotics to Puncta

The Evidence: Research Supporting the Axis

Once these molecules enter systemic circulation, they travel throughout the body, triggering a chronic, low-grade inflammatory state. This persistent inflammation can be particularly damaging to the delicate tissues of the anterior segment of the eye, including the meibomian glands, conjunctiva, and tear ducts. The circulating inflammatory mediators activate resident immune cells in these tissues, creating a cycle of inflammation and damage that makes conditions like Dry Eye Disease (DED) and Meibomian Gland Dysfunction (MGD) more severe and difficult to manage with topical treatments alone. (5)

The evidence for this connection is mounting. Studies have shown that patients with DED exhibit alterations in their gut microbiota, including a decreased abundance of beneficial bacteria that produce anti-inflammatory Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs). (5) Conversely, therapies targeting the gut, such as probiotic supplementation, have been shown to improve symptoms in some patients with dry eye and even conditions like chalazion. ,sup>(7) Furthermore, a faecal microbial transplant has been shown to improve DED symptoms in patients with immune-mediated dry eye, which further validates the connection. (7)

The influence of the gut microbiome extends to other ocular conditions as well, like Glaucoma and Diabetic Retinopathy. (7) In autoimmune uveitis, gut commensals may activate T cells that can attack retinal proteins. (6) Inflammation at the intestinal mucosa may increase gut permeability, allowing microbial products to travel to the eye. Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) has also been linked to gut dysbiosis, which can induce retinal inflammation. (4) Even Primary Open Angle Glaucoma (POAG) has a potential link, with some studies suggesting that bacterial colonizers like Helicobacter pylori can increase intraocular pressure and cause damage to the optic nerve through inflammatory cytokines. (1)

| Ocular Disease | Proposed Gut-Eye Axis Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Dry Eye Disease (DED) & MGD | Gut dysbiosis leads to systemic inflammation, which targets the meibomian glands and ocular surface. |

| Autoimmune Uveitis | Gut commensals activate T cells that can travel to the eye, leading to inflammation and retinal damage. |

| Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) | Gut dysbiosis, particularly from high-fat diets, can induce retinal inflammation. |

| Primary Open Angle Glaucoma (POAG) | Bacteria like H. pylori may release toxins that travel to the optic nerve, causing damage. |

Table 1: Clinical Connections: Gut Dysbiosis and Ocular Diseases

A Holistic Approach: Food for Gut and Eye Health

Given the gut-eye axis, a holistic approach to eye care may include dietary changes to support a healthy microbiome. Incorporating foods rich in probiotics, which introduce beneficial bacteria, can help restore balance. Examples include curd, yogurt, fermented rice, and kefir. For prebiotics, which nourish existing beneficial gut bacteria, embrace foods like green leafy vegetables, bananas, onions, garlic, oats, and legumes. (3)

The future of optometry may well involve a greater emphasis on nutritional counselling and a collaborative approach with gastroenterologists to truly get to the root of the ocular discomfort of the patient.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the concept of the gut-eye axis represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of ocular health. It is a new way of looking at eye health, showing us that diseases like dry eye and glaucoma are not just local issues, but can be symptoms of a deeper, systemic problem in the gut. By focusing on a holistic approach that includes diet and addressing inflammation from the inside out, we can get to the root cause. This new perspective is not only fascinating but also opens a powerful new path for eye care, proving that what is happening in your gut has a direct effect on your vision.

References

- Baim, A. D., Movahedan, A., Farooq, A. V., & Skondra, D. (2019). The microbiome and ophthalmic disease. Experimental Biology and Medicine, 244(6), 419-429.

- Campagnoli, L. I. M., Varesi, A., Barbieri, A., Marchesi, N., & Pascale, A. (2023). Targeting the gut–eye axis: An emerging strategy to face ocular diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(17), 13338.

- Markowiak, P., & Śliżewska, K. (2017). Effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on human health. Nutrients, 9(9), 1021.

- Lin, P. (2019). Importance of the intestinal microbiota in ocular inflammatory diseases: A review. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology, 47(3), 418-422.

- Watane, A., Raolji, S., Cavuoto, K., & Galor, A. (2022). Microbiome and immune-mediated dry eye: a review. BMJ open ophthalmology, 7(1).

- Zárate-Bladés, C. R., Horai, R., & Caspi, R. R. (2016). Regulation of Autoimmunity by the Microbiome. DNA and Cell Biology, 35(9), 455-458.

- Zheng, W., Su, M., Hong, N., & Ye, P. (2025). Gut-eye axis. Advances in Ophthalmology Practice and Research.

Author:-

Shruti Dagar is an Assistant Professor and consultant optometrist at Sankara College of Optometry, Ludhiana. With a strong background in both clinical practice and academia, she excels at mentoring students, conducting impactful research, and specializing in low vision rehabilitation. She earned her Master of Optometry degree from The Sankara Nethralaya Academy, providing her with the foundation for her expertise in clinical care and education. She is passionate about leveraging her expertise to improve patient care and advance optometric education.

Recent Comments