Kristi Sharma, M.Optom.

Education Engagement Manager, Vision Science Academy, Guwahati, India

In our digital age, screens are everywhere, from smartphones and computers to tablets and televisions. These devices have become integral parts of our daily lives, but how are they affecting the way our brains process visual information? With the rapid rise of screen usage, it is essential to understand the impact these digital devices are having on our brain’s visual processing capabilities.

Visual Information Processing

Visual information processing begins when light enters the eye, hits the retina which contains photoreceptor cells called rods and cones that convert light into electrical signals. These signals travel through the optic nerve to the brain, where the visual cortex processes the information. The brain then interprets the signals to create the images that we perceive in real-time.(1)

Effects of Digital Devices on Visual Information Processing

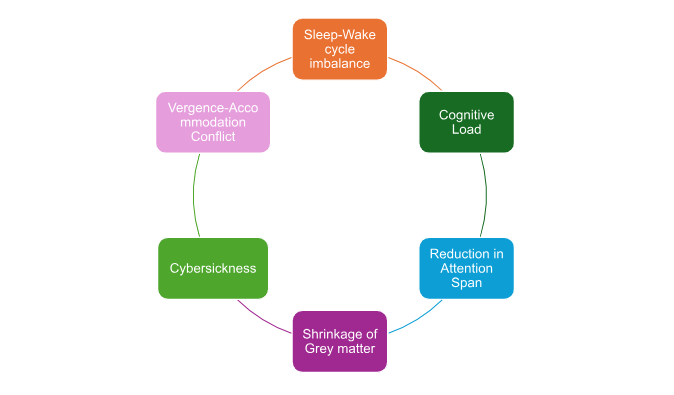

One of the most significant effects of digital devices on the brain’s visual processing is the exposure to blue light. Digital screens emit a significant amount of blue light, which has a shorter wavelength and higher energy than other colours. While blue light is not inherently harmful in small doses, excessive exposure, especially during the evening, can disrupt our circadian rhythm (the natural sleep-wake cycle). The brain interprets blue light as daylight, inhibiting the production of melatonin, the hormone responsible for sleep. This disruption can lead to difficulty falling asleep, poor sleep quality, and even long-term cognitive effects like memory issues and difficulty concentrating.(2)

Secondly, the increasing cognitive load. Our brains were not designed to process the overwhelming amount of visual stimuli we encounter on digital screens every day. This ‘information overload’ can put a strain on our cognitive processing system. When we multitask between apps, websites, etc., our brains are required to shift focus repeatedly. This constant switching can lead to cognitive fatigue, reducing our ability to focus, process information effectively, and retain memories.(3)

Constant screen usage also impacts our attention span. Our brains are not used to processing information in the fragmented manner that digital devices demand. Traditional reading or watching provides a steady stream of visual information, especially with constant notifications and multitasking. This affects the brain’s ability to concentrate deeply on tasks, retain information and make thoughtful decisions. (4,5)

Additionally, high screen time has been associated with changes in brain regions responsible for visual processing. Studies indicate that excessive screen use can lead to reduced grey matter volume and altered connectivity in areas like the occipital cortex, which may affect how visual information is interpreted.(6)

Extended exposure to digital screens, particularly those displaying motion-rich content, can lead to a phenomenon known as cybersickness. This condition manifests with symptoms akin to motion sickness, such as dizziness, nausea, and disorientation. The underlying cause is primarily attributed to a sensory conflict between the visual and vestibular systems. When engaging with dynamic screen content, there is a visual-vestibular mismatch. This mismatch can create a false sensation of self-motion, known as vection, where individuals feel as though they are moving despite being stationary. (7,8)

In natural viewing conditions, vergence and accommodation are synchronised. When we look at an object nearby, our eyes converge and the lenses accommodate to focus on it. This coordination ensures a clear and single image. However, in virtual reality and 3-dimensional environments, this harmony is disrupted. While the eyes may converge on a virtual object that appears close, the actual focal distance remains fixed at the screen’s position, typically a few centimetres away. This discrepancy forces the visual system into an unnatural state, leading to discomfort and visual fatigue.(9)

Image: Ways in which digital devices affect visual processing in the brain

Mitigation Strategies

The ill effects of digital devices and screen-exposure can be mitigated by following some basic strategies. Eye care strategies include adopting the frequently advised 20-20-20 rule, regular blinking, adjustment of screen settings and position, along with the use of proper lighting.(10) Adjustments are needed in terms of cognitive and lifestyle modifications as well. Digital screens should be avoided for at least an hour before sleeping. Practising mindfulness can improve focus and reduce stress, counteracting the cognitive overload from excessive digital consumption. We should allocate specific times to unplug from digital devices, allowing the brain to rest and recover. Pursuing hobbies that don’t involve screens, such as reading physical books or painting, can help to stimulate areas of the brain in a healthy way. (11)

References:

- Alan Woodruff. Visual Perception. The University of Queensland. https://qbi.uq.edu.au/brain/cognition-and-behaviour/visual-perception

- Wahl, S., Engelhardt, M., Schaupp, P., Lappe, C., & Ivanov, I. V. (2019). The inner clock-Blue light sets the human rhythm. Journal of biophotonics, 12(12), e201900102. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbio.201900102

- Skulmowski, A., & Xu, K. M. (2022). Understanding cognitive load in digital and online learning: A new perspective on extraneous cognitive load. Educational psychology review, 34(1), 171-196.

- Alaparthi, K. (2024). Technology and Digital Media’s Impact on Attention Span in Teenagers and Young Adults. Available at SSRN 4872178.

- Sahu, D. P., Taywade, M., Malla, P. S., Singh, P. K., Jasti, P., Singh, P., … & Gupta, K. (2024). Screen time among medical and nursing students and its correlation with sleep quality and attention span: a cross-sectional study. Cureus, 16(4).

- Manwell, L. A., Tadros, M., Ciccarelli, T. M., & Eikelboom, R. (2022). Digital dementia in the internet generation: excessive screen time during brain development will increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in adulthood. Journal of integrative neuroscience, 21(1), 28.

- Tian, N., Lopes, P., & Boulic, R. (2022). A review of cybersickness in head-mounted displays: raising attention to individual susceptibility. Virtual Reality, 26(4), 1409-1441.

- Koch, A., Cascorbi, I., Westhofen, M., Dafotakis, M., Klapa, S., & Kuhtz-Buschbeck, J. P. (2018). The Neurophysiology and Treatment of Motion Sickness. Deutsches Arzteblatt international, 115(41), 687–696. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2018.0687

- Chellapan, T., Daud, N. B. M., & Narayanasamy, S. (2023). Smartphone Use on Accommodation and Vergence Parameters: A Systematic Review. Malaysian Journal of Medicine & Health Sciences, 19(3).

- Talens-Estarelles, C., García-Marqués, J. V., Cerviño, A., & García-Lázaro, S. (2022). Determining the best management strategy for preventing short-term effects of digital display use on dry eyes. Eye & Contact Lens, 48(10), 416-423

- Lauren Thomann. (2024). ‘Popcorn Brain’ Is Shortening Your Attention Span—Here’s How to Refocus, Psychologists Explain. Real Simple. https://www.realsimple.com/popcorn-brain-shortening-attention-span-refocus-8600288

About the Author

Kristi Sharma is a Master of Optometry with a clinical research expertise in Teleophthalmology. She currently works as an Education Engagement Manager at Vision Science Academy. She has published a number of scientific blog articles in the past 5 years and aspires to continue contributing significantly in the domain of ophthalmic research and writing.

Recent Comments